Throwing the kitchen sink at the NHS deficit: will it work?

22 February 2016

Despite huge efforts at both national and local level, the provider sector deficit continues to grow. The NHS was only given a real term increase in its funding for 2016/17 and 2017/18 in exchange for a commitment to return the sector quickly to balance, so the deteriorating financial position raises questions about how and when this will be possible.

It is understandable that the Department of Health and soon-to-be NHS Improvement felt compelled, and were requested by the Treasury, to take unprecedented steps to address the financial situation. However, what seems less clear is whether all this will actually work.

Current measures include: the introduction of revenue and capital control totals, previously an essential pillar of foundation trust freedoms; asking finance directors to pull exceptional levers to improve their balance sheet; and restricting capital expenditure to name just three. Taken together, these actions will no doubt make a dent in the deficit, but it is ambitious to suggest that it will be enough to bring the sector back in to balance next year.

Let’s take the introduction of revenue control totals as an example. This requested all providers to make a step change improvement in their financial plans for 2016/17, either to improve a planned surplus or reduce a deficit position.

There has been a perception from the centre that boards were no longer exercised by being in deficit as long as they were in the middle of the pack. From this perspective, introducing trust specific control totals has the potential to break this cycle, providing a clear focus for every provider and removing uncertainty about what level of deficit would be tolerated. Essentially, it would compel providers to stop hiding behind another’s deficit, if you indeed thought that was happening.

Turning to the numbers, the justification for introducing control totals is on more shaky ground. Providers have been given a 2.5% efficiency stretch on their 2015/16 financial forecast, translating for some to a 4-6% cost improvement plan (compared to a current average of under 3%), which is a substantial ask for any organisation. For most providers, the financial incentive in signing up to the target is the (conditional) receipt of a slice of the £1.8bn sustainability fund.

The response from the sector has been mixed. Our estimate is that around two thirds of providers will have accepted the control total they have been allocated but most have done so citing a long list of downside risks given the degree of stretch being asked for.

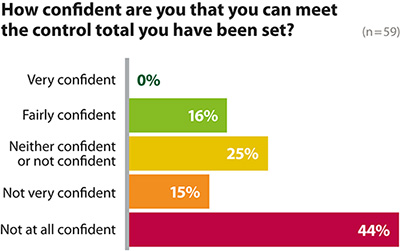

It is normal for financial plans to come with some downside risks but most finance directors will tell you that the risks underpinning their control total are substantial. This suggests that although provider boards have signed up, the majority are concerned about how deliverable it is – our recent survey of finance directors highlights that 60 per cent of providers are not confident they could meet their target.

If any of the downside risks were to materialise – for example a contract negotiation with a CCG or specialised commissioning team which does not quite go to plan – trusts would miss their target, in theory preventing them from receiving their share of sustainability funding.

Control totals also introduce difficult governance issues for boards. Foundation trust directors have a duty to exercise independent judgement, and are responsible for undertaking rigorous appraisal of financial plans. There would be clear governance implications for boards who agree to a control total which they consider, or are concerned, is undeliverable. If the trust subsequently fails to meet this target, it could be considered a governance failure of the board, potentially carrying regulatory implications for those responsible. This might explain why when Monitor and the Trust Development Authority asked providers to do something similar last year to improve their in-year position for 2015/16, few boards could agree to do so.

These measures create a whole host of behavioural, governance and reputational issues for local leaders – one finance director has already spoken up to say that their objectivity, integrity and professional competence is at stake.

What needs to be done?

In order to better support local organisations and leaders through this, and to maximise chances of these (and any future) measures actually having the desired affect, we need three things.

- Honesty: some providers feel they have been given with no option other than accept a control total they know to be undeliverable. Not signing up would run the risk of not being able to access essential DH loans, or face the full wrath of contract fines for any breaches in quality and access standards. There needs to be space for providers to agree a deliverable but stretching target, otherwise boards will feel compelled to sign up to a target they know is not possible.

- Clarity: we need to understand whether the current approach is an indication of a permanent shift in regulatory approach, or an exceptional set of measures for 2016/17. The centre needs to be clear about what the trigger(s) will be for removing control totals – this is key to understanding what underpins NHS Improvement’s promise of ‘earned autonomy'.

- Reaffirming the role of the board: it is clear that provider boards, together with their local partners, are best placed to make decisions based on local needs. The centre needs to be careful not to disempower providers, at the very time they are being encouraged to be bold in the development of multi-year sustainability and transformation plans.

It might be understandable that the national level has asked provider leaders to throw everything they can at addressing the deficit, but we might need to contemplate what happens if all these measures are not enough. Doing nothing was not an option, but asking for too much also carries risk.

This blog is also published in HSJ.